By Jeffrey J. Spina-Jennings, Esq., Gould Cooksey Fennell, PLLC, Vero Beach, Florida

As a result of the recent restructuring of Patagonia utilizing a social welfare organization (“501(c)(4)”) there is a revitalization of discussions regarding whether a 501(c)(4) may be an appropriate structure to carry out a client’s charitable objectives. News reports have tended to place emphasis on a 501(c)(4)’s ability to engage in political activities and lobby. While lobbying is a unique characteristic that should be noted, estate planners should be familiar with other aspects of a 501(c)(4). This article will provide a primer that contextualizes those aspects of a 501(c)(4) compared to another commonly used structure, the private foundation. [1]

What is a 501(c)(4)?

As defined by the Code[2], a 501(c)(4) is an organization[3] which is operated exclusively for: (i) the promotion of social welfare, or (ii) a local association of employees, the membership of which is limited to the employees of a designated person or persons in a particular municipality, and the net earnings of which are devoted exclusively to charitable, educational, or recreational purposes.[4]

At a minimum, an estate planner would need to be familiar with the “social welfare” operational requirement as that is the most appropriate way in which our clients would achieve 501(c)(4) status for an entity. What does it mean for an organization to be operated for the promotion of social welfare? According to the Regulations, the determination is based on whether the organization is being operated for the “common good and general welfare of the people of the community” or “for the purposes of bringing about civic betterments and social improvements.”[5] This is very fact specific, but for illustrative purposes, if the client desires to engage in the same activities as a private foundation it would

likewise qualify as a 501(c)(4). Two things that clearly do not qualify as “social welfare” as stated by the Regulations are: (i) direct or indirect participation or intervention in political campaigns, or (ii) operation as a social club for the benefit, pleasure, or recreation of its members.[6]

How to Apply for Tax Exempt Status as a 501(c)(4)?

Estate planners should be familiar with the requirement of a private foundation to file a Form 1023 within twenty-seven (27) months from the date of its formation in order to obtain tax-exempt status from inception.[7] This is all conditioned on the IRS‘[8] approval of such tax-exempt status. The steps to

operate as a 501(c)(4) are relatively simple in comparison, as the organization is solely required to notify the IRS of its intent to operate as a 501(c)(4).[9] To comply with this requirement, a Form 8976 must be filed electronically within sixty (60) days of the organization’s formation. The IRS will return an acknowledgement that it received the Form 8976.

A 501(c)(4) can request formal recognition of status through the optional filing of a Form 1024-A. The benefits of filing a Form 1024-A would include public recognition of 501(c)(4) status and potential exemption from state taxes. Florida, for instance, would require a determination letter if applying for exemption from sales and use taxes.

What is the Deductibility of a Transfer to a 501(c)(4) for Income Tax, Gift Tax, and Estate Tax Purposes?

Unlike a private foundation, contributions to a 501(c)(4) cannot be deducted for federal income tax purposes.[10] This is often an important consideration for an estate planner when determining the charitable structure that would best serve a client’s charitable goals during his or her lifetime. For transfers at death, it is commonly known that a federal estate tax deduction is available for contributions to private foundations; however, no such deduction is available for contributions to a 501(c)(4).[11] Notwithstanding the above, a contribution to a 501(c)(4) is not treated as a gift for federal gift tax purposes, which was intended to eliminate any potential ambiguity in the gift tax realm.[12] For the reasons stated above, if a 501(c)(4) is the desired charitable structure for a client, it is advised that any transfers to such 501(c)(4) be done prior to a client’s death.

What Level of Public Disclosure is a 501(c)(4) Subjected To?

Client privacy is an important aspect when it comes to private foundations. A private foundation, generally, is subject to high levels of public disclosure, which includes public access to its required annual Form 990 or Form 990-EZ and its application for exempt status. For a 501(c)(4) is, however, the required notice of intent to operate through the filing of a Form 8976 is not available to the public. A 501(c)(4) is, however, still required to file an annual Form 990 or Form 990-EZ, which is available for public inspection. In addition to Form 990, the 501(c)(4) will also need to keep its Form 1024-A available for public inspection if it filed such Form 1024-A. Important to note for client privacy purposes, a 501(c) (4) is not required to disclose the names of its donors.[13] However, depending on what state the 501(c)(4) operates, such information may be requested by such state, but public disclosure of donor information is still a grey area which is arguably invalid on federal or state constitutional grounds.[14] Florida does not currently expand any required federal disclosures, which may mean there is a desire by the Florida legislature to further protect donor privacy in Florida.

What Taxes Apply to a 501(c)(4)?

One of the main concerns estate planners will discuss with their clients prior to forming a private foundation is the imposition of excise taxes under Code Sections 4941 through 4945. As a reminder for those familiar, the acts that trigger an excise tax include: (i) taxes on the private foundation’s net investment income,[15] (ii) prohibitions on self-dealing transactions,[16] (iii) failure to make the required five percent (5%) qualifying distributions to charities,[17] (iv) prohibition on excess business holdings,[18] (v) prohibition on holding jeopardizing investments,[19] and (vi) taxable expenditures,[20] none of which apply to a 501(c)(4).[21]

Despite the non-application of the above excise taxes, a 501(c)(4) is not completely exempt from all forms of taxation. Importantly, the unrelated business income tax still applies to a 501(c)(4), and therefore, a 501(c)(4) should be mindful of whether an income raising activity would trigger the application of these rules.[22] Furthermore, taxes on excess benefit transactions where the 501(c)(4) provides an economic benefit, either directly or indirectly, to any disqualified person will apply if the value of the economic benefit exceeds the value of the consideration received.[23]

The last tax that may apply to a 501(c)(4) is situational and dependent on whether political expenditures are made by the 501(c)(4), namely the tax imposed under Code Section 527(f). If Code Section 527(f) applies to the 501(c)(4), such tax will generally be calculated based on the lesser of: (i) the organization’s net investment income for the taxable year, or (ii) the aggregate amount expended for an “exempt function.” An “exempt function” generally includes influencing or attempting to influence the selection, nomination, election, or appointment of an individual into a political office or political organization.[24] The determination of whether something is expended for an “exempt function” is extremely fact dependent and any political expenditures should be carefully reviewed to determine whether a potential expenditure falls within the purview of this tax.

Is Compensation Allowed to a Related Party?

A common benefit enjoyed by private foundations is the ability to pay reasonable compensation to employees and board members, even if they are related to a substantial contributor. If the private foundation pays compensation that is deemed “unreasonable” to certain related parties the consequences are severe.[25]

In the case of a 501(c)(4), compensation is permitted to a related party, however, as mentioned earlier in this article, the excess benefit transaction rules still apply to a 501(c)(4), and thus, a determination of “reasonable compensation” by the 501(c)(4) when making payments to a related party is still needed. [26] A situation that may commonly arise for an estate planner is where a client creates a 501(c)(4) with his or her children or grandchildren on the board of directors and such child or grandchild draws a salary. It is, therefore, still recommended that the same steps that would be undertaken to show reasonable compensation for a private foundation be followed when determining compensation by a 501(c)(4) to a related party to avoid a tax on potential excess benefit transactions.

How Much Lobbying Can a 501(c)(4) Engage In?

It is widely known that a private foundation is prohibited from making direct or indirect political expenditures. An estate planner may have a client who desires to make political expenditures to further his or her charitable goals. This can be accomplished with a 501(c)(4) where lobbying is permitted in an unlimited amount, provided such lobbying is directly related to the exempt purpose, and so long as such activity is not for private gain.[27]

Political campaign activities are more restricted if such political campaigning prevents the organization from being “primarily engaged” in social welfare work.[28] One of the most high profile instances of a 501(c)(4) engaging in political campaigning relates to Citizens United’s political activities and the subsequent approval by the Supreme Court of such activities, which resulted in a more widespread use of 501(c) (4)s being established for political purposes.[29] While a 501(c) (4) can engage in such activities in order to determine the form and method of political expenditures, federal and state election laws should be carefully reviewed.

There is no safe harbor or test to determine how much political campaigning disqualifies a 501(c)(4). In theory, forty nine percent (49%) is as far as an organization may go; however, much like Icarus, a 501(c)(4) may get burned. Forty percent (40%) is generally floated around as a safer recommendation.

Can a 501(c)(4) Be Used To Remove Assets From A Client’s Taxable Estate?

While a transfer to a 501(c)(4) is not treated as a taxable gift, assets that are directed from a client to a 501(c)(4) from his or her estate will receive no offsetting estate tax deduction. Therefore, attempting to transfer assets to a 501(c)(4) at a client’s death would be inefficient from a tax perspective. Utilizing the tax-free transfer during a client’s life, it is possible to remove assets from a client’s taxable estate prior to such client’s death. An estate planner should be cautious in how the transfer and the 501(c)(4) are structured as there are several ways in which the IRS could attempt to claw assets from a 501(c) (4) into a client’s taxable estate. As will be discussed below, the most problematic provisions an estate planner should be concerned over are the usual suspects, which include Code Sections 2035 (transfers within three years of death), 2036 (retained interests) and 2038 (revocable transfers).

A major inclusion risk that should be considered is whether the client has a retained interest in the assets held by the 501(c) (4) under Code Section 2036. The IRS has held previously that assets transferred to a private foundation could be includible in a taxpayer’s gross estate because of a retained right as a director, or officer with a similar position of authority, who can direct the disposition of the private foundation’s funds for charitable purposes.[30] While in the private foundation context there would be an offsetting charitable deduction, there is no such deduction for transfers to a 501(c)(4). A similar approach could likely be utilized through Code Section 2038. Therefore, estate planners should exercise caution when planning the organizational structure of the 501(c)(4) and should consider potential avenues of inclusion to prevent the potentially disastrous result of inadvertently increasing a client’s taxable estate without any offsetting deduction. Ideally, an independent board of directors or trustee would provide oversight and control over the organizational structure or ability to direct assets to remove potential inclusion issues under Code Sections 2036 or 2038.

Assuming the concerns regarding Code Sections 2036 and 2038 are addressed, estate planners are all too familiar with the risk of inclusion for assets transferred or strings released within three years of death. This includes transfers or strings released over assets that were otherwise includable under Code Sections 2036, 2037, 2038, or 2042.[31] Notably, if the client’s position as director or trustee of the 501(c)(4) would have caused inclusion, a resignation of such position would result in the client needing to survive three years past the date of such relinquishment. Therefore, it is important for the estate planner drafting the 501(c)(4) or transferring assets to an established 501(c)(4) to keep potential inclusion issues in mind, especially in light of the disallowance of an estate tax deduction.

Can An Operating Business Be Transferred to A 501(c)(4)?

Unlike a private foundation, a 501(c)(4) can hold an operating business as an underlying asset without any risk of subjecting it to a tax on excess business holdings.[32] It is important to note that the 501(c)(4) should be careful with its business holdings to prevent inuring to the benefit of a private person. That being the case, it may be an efficient structure to utilize the earnings of the underlying operating entity to potentially generate tax-free income (subject to the rules relating to unrelated trade or business income that may apply) which further benefits a client’s charitable goals. Further, the underlying business can later be sold without incurring tax, providing an efficient exit strategy for a client. It is important to note that a transfer of an operating business into a 501(c)(4) should not be done in anticipation of a sale of such business to prevent application of the assignment of income doctrine.

Can a Private Foundation Be Converted to a 501(c)(4)?

Assuming a client already has a private foundation established they may inquire as to whether his or her existing private foundation can be converted into a 501(c)(4). A private foundation is unable to convert to a 501(c)(4) without first dissolving.[33] Furthermore, a dissolution transfer to a 501(c)(4) will trigger a tax to the private foundation making such dissolution distribution.[34] Therefore, if a client has a private foundation currently and is contemplating a 501(c)(4) he or she would need to consider establishing a new organization that would qualify as a 501(c)(4) and contributing additional assets to such organization from his or her personal accounts.

Conclusion

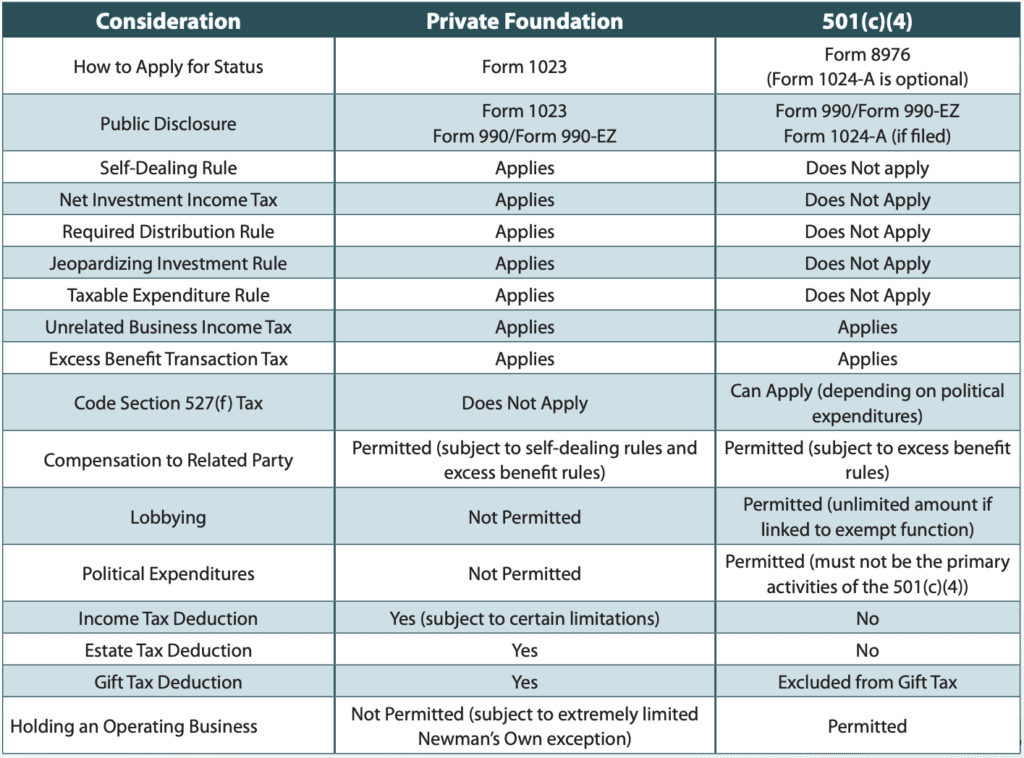

In certain instances, a 501(c)(4) is a tool that may provide an opportunity to facilitate a client’s charitable goals. Likely, this structure is the most appealing to high-net-worth clients where an income tax deduction may not necessarily be crucial, or to clients who have operating businesses they would like to divest from and utilize the earnings of such business to further their charitable goals. Below is a chart summarizing several of the important distinctions between a private foundation and a 501(c)(4).[35]

Endnotes:

1 All references to “private foundation” have the same meaning as defined

in IRC Section 509.

2 For purposes of this Article references to the “Code” refers to the Internal

Revenue Code of 1986 and all references to the “Regulations” refers to

regulations promulgated by the United States Treasury interpreting the Code.

3 For purposes of this Article “organization” refers to any organizational

structure, including a trust or corporation which can qualify as a tax exempt

entity under IRC Section 501(c)(4).

4 IRC Section 501(c)(4).

5 Treas. Reg. Section 1.501(c)(4)-1(a)(2)(i) (2023).

6 Treas. Reg. Section 1.501(c)(4)-1(a)(2)(ii) (2023).

7 IRC Section 508 (2023).

8 All references to “IRS” refer to the Internal Revenue Service.

9 IRC Section 506 (2023).

10 IRC Section 170 (2023).

11 IRC Section 2055(a)(2) (2023).

12 IRC Section 2501(a)(6) (2023).

13 See, Treas. Reg. Section 1.6033-2(a)(2)(ii)(F) (Disclosure of donor information

for contributions greater than $5,000 is generally only required of a 501(c)(3)).

14 See Ams. for Prosperity Found. v. Bonta, 141 S. Ct. 2373 (2021) (overturning

a Ninth Circuit decision and holding California’s disclosure requirements

regarding donors was facially invalid on First Amendment grounds).

15 IRC Section 4940 (2023).

16 IRC Section 4941 (2023).

17 IRC Section 4942 (2023).

18 IRC Section 4943 (2023).

19 IRC Section 4944 (2023).

20 IRC Section 4945 (2023).

21 All taxes mentioned in endnotes 16 through 20 only apply to “private

foundations.”

22 IRC Section 511 (2023).

23 IRC Section 4958 (2023).

24 IRC Section 527(e)(2) (2023).

25 See IRC Section 4941 and the accompanying regulations.

26 See IRC Section 4958 and the accompanying regulations.

27 See Treas. Reg. Section 1.501(c)(4)-1(a)(2)(ii), Rev. Rul. 67-293, 1967-2 C.B.

185, and Rev. Rul. 71-530, 1971-2 C.B. 237.

28 Treas. Reg. Section 1.501(c)(4)-1(a)(2)(ii) (2023).

29 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010).

30 Rev. Rul. 72-552, 1972-2 C.B. 215; IRC Section 2036(a)(2) (2023).

31 IRC Section 2035(b) (2023).

32 Generally, IRC Section 4943 prohibits a private foundation from holding

an operating business. IRC Section 4943(g) known as the “Newman’s Own”

exception does allow for a private foundation to hold a one hundred percent

(100%) interest in an operating business provided the donor and all related

parties completely relinquish all interests over such operating business. The

Newman’s Own exception is very restrictive and not commonly utilized by

private foundations.

33 See Generally, Rev. Proc. 2017-5 Setting Procedures for Certain

Determination Letters on Exempt Status Under Section 501(c)(3).

34 IRC Section 507 (2023).

35 The foregoing materials are for solely educational purposes and do not

constitute U.S. tax or other legal advice. The laws discussed herein are complex,

and an appropriate course of action is dependent upon all applicable laws,

rules and regulations as well as the pertinent facts and circumstances. Any

person interested in forming a 501(c)(4) or private foundation, or making

charitable gifts to a 501(c)(4) or private foundation, should consult with his or

her professional advisors.

This article was originally published in the Winter, 2024 issue of ActionLine, a Florida Bar Real Property and Trust Law Section publication.